Emily Warn is a widely published American poet and essayist. She recently served as founding editor of www.poetryfoundation.org, a Webby Award winning website. She sat down with E.A. (Annie) Stewart to talk about Bone-mend and Salt, Book 1 in her 13th century historical fiction series, Accidental Heretics.

#

Emily Warn: Why did you choose to write about the 13th century?

Annie Stewart: Through a random event at Powell Books. Doesn’t everyone who wanders around Powell Books experience at least one life-changing event?

Annie Stewart: Through a random event at Powell Books. Doesn’t everyone who wanders around Powell Books experience at least one life-changing event?

I was sketching a story of intrigue and revenge, arising from some event during the Third Crusade. But I hadn’t decided where to place the story—what country? Exactly what time period? While browsing the history aisle I found Chasing the Heretics: A Modern Journey through the Medieval Languedoc. My first thought was, “I always wanted to know more about the Albigensian Crusade, when they burned all the heretics.” No, really, I said that aloud while standing in the stacks. Intrigues between popes and kings! What a great basis for a revenge story.

Over time, the more I learned about the Languedoc culture in medieval time, the more I realized that everything I knew about medieval northern Europe was useless for this story. But as it turned out, having to toss everything I thought I knew ended up spawning more creativity.

EW: I admire how you integrated medieval and current times, including the nature of language, gender roles, and technology. How did you manage that?

EAS: I have a friend who’s a medievalist, and she always says, “We can’t really understand the medieval mind.”

Well, before I could try to understand, I first had to make sure my writing didn’t sound stiff or like a Walter Scott imitation. Several draft of early chapters were sent to the garbage dump in the sky, until I could get rid of awkward sentences.

Then, since I wanted early-13th century culture to be part of the story, I had to prevent late-13th and 14th century technologies from creeping in. It was relatively easy to make sure the armor and weapons were of that earlier time. Other technologies were harder to manage. For example, people didn’t have clocks, or a concept of minutes and hours. And ringing of church bells on canonical hours wasn’t prevalent then. So I created a list of words to search repeatedly, to make sure those words didn’t appear: hour, minute, second, time.

EW: I could relate to Isabella as a strong female, and so contemporary a character. Is she true to the 13th century?

EAS: When I began this story, I tussled with gender and class issues. I came out of the Sixties and Seventies feminist quest to find ourselves in history, but I fear didacticism worse than anachronism. Characters like Isabella, Katelina, and Chrétien in Accidental Heretics involved a lot of research into cultural norms of the time. And that research continues.

EAS: When I began this story, I tussled with gender and class issues. I came out of the Sixties and Seventies feminist quest to find ourselves in history, but I fear didacticism worse than anachronism. Characters like Isabella, Katelina, and Chrétien in Accidental Heretics involved a lot of research into cultural norms of the time. And that research continues.

For example, the overall story of the Accidental Heretics needed a strong female character who seeks to keep charge of her own fate. That’s Isabella in Bone-mend and Salt—from country nobility, but impoverished and besieged by history. I wanted to make Isabella as true to her time as possible. So, in the story, Isabella has freewill with regards to marriage—up until the invasion of the northern French stomps on local customs.

I think part of what makes Isabella so compelling (and why we want to identify with her) is that she wants to remain true to herself, in spite of the revolutionary shift in social norms that the French invasion brought with it.

EW: I think of that period as male dominated, so isn’t it a stretch of truth to have strong female characters?

EAS: I couldn’t see how to build a complex story based on a kitchen worker, and I’m not interested in princesses saved by gallant knights. To start, I posited that women from more privileged classes had significant roles because the men were always off on a crusade. As I dug into the cultural history of the Languedoc, from before the French invasion, I found a lot of evidence that women in that culture didn’t have the same “chattel” status as in northern Europe: they could inherit; they had significant leadership roles in their households and communities.

Then I found Frederic Cheyette’s study of Ermengarde of Narbonne, which confirmed what I had surmised. Women held real power, moved freely, led armies, negotiated with other leaders.

And as Isabella reminds us in Bone-mend and Salt, Eleanor of Aquitaine led an army in the Crusader Kingdoms (before she married Henry II). The wife of Simon de Montfort led a thousand troops to join him in the Languedoc. Women had roles other than laundresses in the baggage train.

To start, see the blog post topic: “Another Entitled Woman Dressed as a Man?”

EW: Wow. You did a lot of historical research before you even set pen to paper. How did you manage that?

EAS: I wrote while I was doing the research, instead of waiting. I do love research, but I’m an armchair historian—actually, more of a beach-chair historian. And I don’t want research to get in the way of actual composition.

My medievalist friend helped prevent some humiliating anachronisms. For example, the Fourth Latern Council didn’t occur until 1215, so not all sacraments had the same standing as the Church follows today. The eastern Roman Empire wasn’t called “Byzantine” until the mid-16th century.

EW: In reading your story, I found a lot of parallels between our current, religious-fundamentalist fueled conflicts and papal vs. secular ruler conflict of the 13th century. Did that affect your writing?

EAS: In my early drafts, the series was titled “Crusaders Children,” because I was focused on three characters who inherited a curse from their fathers, who had been crusaders in the Holy Land. As I read more about the Crusader era, I found many historians commenting on the legacy of the European incursion into the Holy Land—for example, how Richard the Lionheart murdered hostages outside Jerusalem, instead of ransoming them as tradition demanded. Richard’s slaughter of hostages perpetuated a series of crises in Christian-Muslim relations.

In the world after 9-11, where we can see how these conflicts have continued over the past millennium, I didn’t feel that I could call the series “Crusaders Children,” because that title seemed to have too much resonance with our current experience. I chose instead to focus the title and the story on the Languedoc crusade in Europe—which was Christians attacking Christians—instead of on the Crusader States in the Middle East. Hence, the Accidental Heretics.

EW: We both worked at Microsoft as technical writers and web managers. What’s it like writing a novel after a long career in technical writing?

EAS: As you know, it’s the many long ten- and twelve-hour days at a place like Microsoft that interfere with other creative work, not the kinds of tasks the job involves. When I had less grueling assignments, I could find time to write fiction. I’ve discovered that I learned a lot in my technical writing career that I use in writing fiction.

Most important, I learned to keep my rear-end in a chair for long stints of time to meet writing goals and deadlines. I already knew that you have to write all the time, not just when the mood calls. Being a tech writer taught me how to make “inspiration” appear on command, and to break work into chunks, so I can set interim goals for what I want to accomplish. A project doesn’t seem so overwhelming when it’s just that day’s assignment.

Also, I’m extremely efficient with the tools that support writing—how to use software that keeps me organized. For a peek into how I use software tools to manage a large novel, see my blog entry (as Annie Pearson): http://wp.me/P2T7Qw-1o

EW: Why did you write this as a series?

EAS: I love to read long, complex stories with many characters whose motivations and personalities drive multiple plots. Because that’s what I like to read, I wanted to explore the long-arc story form—similar to what David Chase or Joss Whedon have done in superior television stories.

And I didn’t want to write serials, like murder mysteries with a recurring main character. In those kinds of serials, the detective (or other main character) reappears from book to book, but the focus of the story in each book isn’t the development of that character. I want a very long story, where you can live with the characters inside the books.

EW: Do you like staging fights and battles, especially medieval ones? How did you fall in love with the fights of the Middle Ages?

EAS: I stage only in the solitary privacy of my work room. I have a personal romance with fighting, but I don’t practice either hand-to-hand combat or siege engineering with trebuchets.

EAS: I stage only in the solitary privacy of my work room. I have a personal romance with fighting, but I don’t practice either hand-to-hand combat or siege engineering with trebuchets.

My introduction to the Middle Ages, beyond Ivanhoe and King Arthur in junior high, was the Royal Shakespeare Company production of the King plays, which were broadcast repeatedly on the PBS station in Portland. Robert Hardy played Prince Hall, and Sean Connery was Hotspur (before he was James Bond). Hence, I love sword fights!

Then I went to school in Ashland, at the time when the fight directors at the Shakespeare Festival first began working on authenticity, similar to how Todd Barton worked on authentic Early Music. Later, I indulged deeply in Taiwan/Hong Kong fight movies, the kind Jackie Chan made when he was a teenager.

In the early 13th century, hand-to-hand fighting with swords in Europe hadn’t progressed to “Three Musketeers” rapiers. Knights were just beginning to move beyond bludgeoning with huge iron swords. Tech-transfer—that is, secrets from Arabic cultures—of better steel manufacture had just begun to filter into Europe. The science of siege was advancing, based on what crusaders learned in the Outremer. Huge siege engines—trebuchets and similar engines—were just being introduced at the time of the Languedoc crusade.

For this book, I took advantage of all that early exposure plus great work from historians of weaponry, armor, and battle deployment, especially the works of Ewart Oakshott, David Nicolle, Jason Vail, Matthew Ballent.

And who doesn’t like to see a trebuchet launching pumpkins and pianos?

###

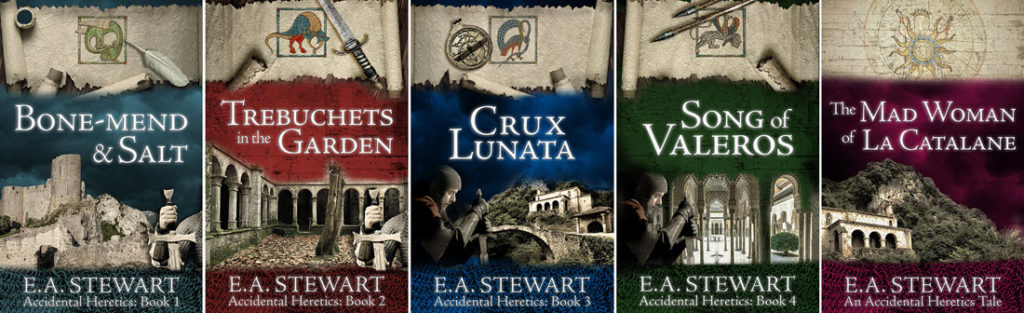

Bone-mend and Salt: Book 1

ISBN: 978-1939423917 (print)

ASIN B00BBXFORY (Kindle)

Trebuchets in the Garden: Book 2

ISBN: 978-1939423924 (print)

ASIN: B00CIVJRLC (Kindle)

Crux Lunata: Book 3

ISBN: 978-1939423177 (print)

ASIN: B017CCI10E (Kindle)

Song of Valeros: Book 4

ISBN: 978-1939423795 (print)

ASIN: B01MYLZT9L (Kindle)